Las ausencias de Miguel Ángel Cruzado / The absences of Miguel Angel Cruzado

He tenido el honor de ser invitado a escribir la introducción al catálogo de la exposición fotográfica “Enmedio 101”, del fotógrafo español Miguel Ángel Cruzado, recientemente galardonado con el premio nacional de fotografía Lux, en su apartado de arquitectura. La primera exposición será este año, 2019, en la Sala San Miguel – Fundación Caja Castellón, España.

Estoy realmente encantado con la invitación.

He aquí mi texto y algunas de las imágenes que serán mostradas en la exposición.

Gracias, Miguel.

Link a un video sobre la colección: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKm4P2mnS9w

I had been honored with the invitation to write the introduction to the catalogue of the photographic exibition “Enmedio 101”, from the Spanish photographer Miguel A. Cruzado, recently prized with the Lux Photographic Award. First exhibition will be this year, 2019, in the Sala San Miguel – Fundación Caja Castellón, Spain.

I am really pleased to do it.

Here is my text and some of the pictures that will be shown in the exibition.

Thanks, Miguel.

Link to a video about the collection: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKm4P2mnS9w

The English text will be found after the Spanish text.

LAS AUSENCIAS DE MIGUEL ÁNGEL CRUZADO

Llevo un buen rato mirando la colección con el privilegio de escrutar las fotos a mis anchas, en casa, con un café en la mano, escuchando la música que me apetece y tirado para atrás en mi silla preferida. No han tardado en empezar a decirme cosas, muchas cosas.

Esto está lleno de ausencias.

Está lleno de la invisibilidad de lo que ya no existe.

Pero son huecos llenos de emociones.

Las emociones se contagian. Las tuyas, las suyas, me traen a la memoria las mías y con ellas la nostalgia de lo que ni tan siquiera sabía que añoraba.

Estos huecos vacíos, como muertos, llenos de memorias que no me pertenecen, me dejan presentir la vida que se les ha escapado. Y puedo comprender el dolor de sus ausencias porque siento el de las que yo guardo.

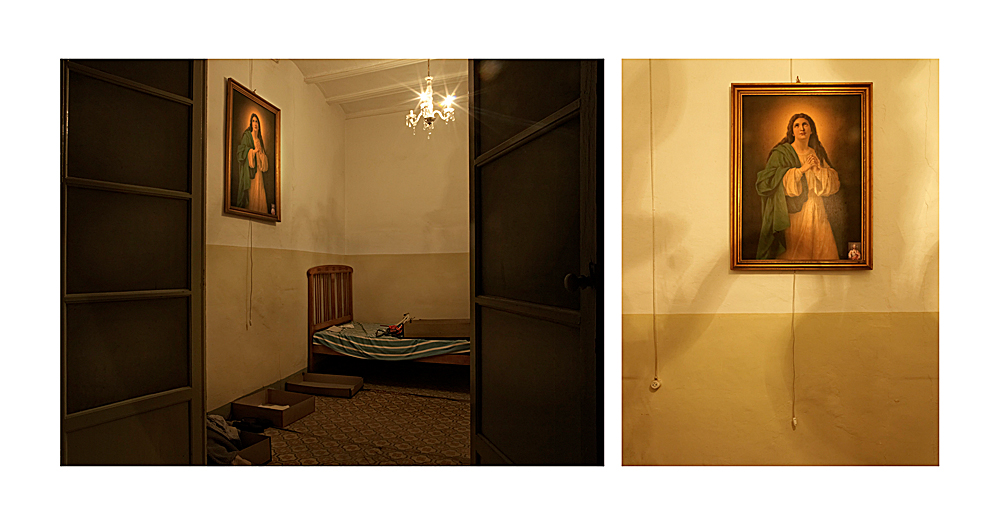

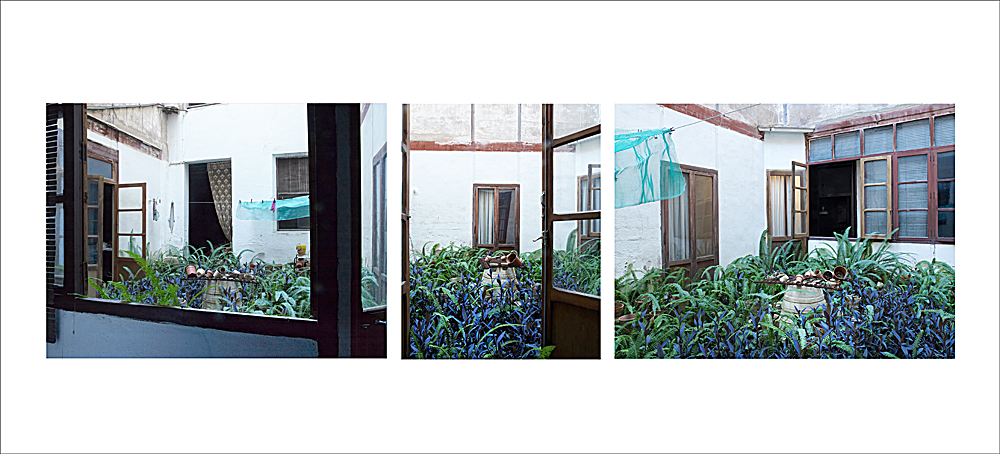

Esto ha dolido –¿eh, Miguel?–, porque los disparos parecen esperar que algo se mueva como siempre. Como cuando allí había voces y tus tías aseaban los pasillos, arreglaban el pequeño jardín, encendían el fuego y había luz en las ventanas. Y ahora las imágenes muestran esa soledad desgarradora, que se ha de sentir para que unas fotos tan poco rebuscadas, tan esenciales, tan mínimas, sean capaces de decir tanto. Estas imágenes de un viejo edificio, de unas ruinas casi, unas arquitecturas miradas como para no ser visto, como para no molestar, pasando de puntillas entre sus fantasmas –tus fantasmas–, son sentimientos que no se pueden disimular. Y lo has hecho bien, porque también nos duelen a los demás. Estos fantasmas los tenemos dentro todos los que ya hemos vivido alguna de esas no deseadas ausencias.

Estas fotos están hechas para aquellos seres humanos que ya pueden decir que han vivido, y no solo que están vivos.

No me extraña que unos trípticos de estas imágenes se hayan llevado los premios Lux de fotografía.

Me sobrecogen.

Para entenderlas es necesario ver, pero no un ver superficial, no un mirar y ya está. Es necesario ese “ver” que mira con más órganos que los ojos, que añade corazón para sentirlas, cerebro para comprenderlas y alma para ponerles vida con nuestra imaginación. De ese modo no solo se entienden las imágenes, también se te comprende a ti. Puede verse a Miguel pasear entre paredes de emociones, buscando las esencias de lo que allí hubo, los restos de ese perfume que te recuerda a alguien querido, y que para ti parece seguir habitando en la memoria de las cosas.

Y para quienes, como yo, conocen bien al Miguel fotógrafo, estas fotos también son un contrasentido.

Son la oposición al fotógrafo controlador, perfeccionista, que buscaba y rebuscaba las luces, que cambiaba focos y contrastes no una, sino otra y otra y otra vez, que matizaba, que ajustaba, reajustaba, componía y recomponía la escena, los bodegones, los escenarios…, con una finura de estilo particular y reconocible. Un auténtico manipulador de los elementos, un profesional que sabe lo que hace y utiliza los recursos de su artesanía.

Y sin embargo aquí no hay nada de eso, de esa preparación, de esa intervención.

Aquí para ti todo estaba en su sitio. Cambiar un detalle era destruir la composición, hacer tambalearse la escena; peor aún: tocar algo era difuminar la pureza de los sentimientos. Todo es exactamente lo que era, todo está como estaba, y tú no has sido más que un testigo de que nada había cambiado. Esto es fotografía en estado puro, esto es mirar hacia fuera con un signo igual. Lo que hay ahí afuera y que captamos, debe corresponderse en el mundo de las emociones con algo que hay dentro de nosotros clavado intensamente, porque sin esa correspondencia, sin ese signo igual, estamos tan muertos como si las imágenes las hubiera capturado una cámara robotizada en cualquier esquina de una ciudad. Y eso no es lo que ocurre aquí.

Esto está vivo y habla.

Pero Miguel, no te escapas a ti mismo. Al final has caído en la trampa y te has metido hasta el cuello en un proceso más incontrolable que lo contrario. La cámara de 30 x 40 cm que te había dejado como despistada en un rincón de tu estudio, la pieza de museo fabricada en 1840 por Louis Pin en las afueras de París, catorce añitos después del nacimiento de la fotografía, ha vuelto a la vida y te ha seducido con sus curvas cuadradas y rotundas. La has acariciado como si fuera la lámpara de Aladino, y ha empezado a regalarnos imágenes al colodión húmedo como si viviéramos en el ayer. Tal vez la cámara sea hermana en el tiempo del edificio 101, con cuyas fotos hemos sido seducidos y raptados nosotros. Los ferrotipos encajan perfectamente entre sus paredes, complementan, ambientan, se integran de modo impensable con lo que pretenden el resto de las imágenes.

Me pregunto cuál de las dos ideas brilló primero, qué llevó a qué, quién inspiro a quién.

De cualquier modo he de aceptar que, haber caído en tu propia trampa, ha sido el acento perfecto para una exposición que, si ya era excepcional, con las muestras al colodión húmedo es toda una referencia.

A diferencia de las fotos del edificio, los viejos ferrotipos me trasladan al pasado, al pasado del edificio y su vida, a “su” pasado. Parece como que puedo vivirlo en los que fueron mis recuerdos, que no son estos. La Virgen en su hornacina, los viejos objetos, cables, sillas, cajas y lámparas, son a tus fotos nuevas del viejo edificio como jóvenes imágenes recién descolgadas… hace más de cien años.

No, estás fotos no son un acta notarial, no son una descripción topográfica de una realidad, no son parte de una memoria administrativa a la que se han grapado.

Al igual que un lápiz sirve para hacer la lista de la compra o para escribir un poema, para dibujar el sueño del más sabio de los hombres o garabatear “mamá” por primera vez, también con una cámara todos esos matices están a disposición de quien ha aprendido a usar los recursos que esconde, para expresar lo que está oculto en sus propios sentimientos y emociones.

Da miedo desnudarse tanto, porque mostramos nuestras debilidades, pero cuando a veces alguien se atreve y lo hace, la vida nos regala con cosas como esta exposición.

Disfrutarla es muy sencillo: párate y mira.

Es muy buena.

Muy buena.

Valentín González

THE ABSENCES OF MIGUEL ANGEL CRUZADO

Here I am, at home, tilted back in my favourite chair, looking at the collection, listening to some good music that catches my fancy, a cup of coffee in hand, with the privilege of scrutinizing the photos at ease. It isn’t long before they started to tell me things, many things.

This is full of absences.

It’s full of the invisibility of what no longer exists.

But, they are hollows replete with emotions.

The emotions are transmitted. Yours, his, bring to mind my own, and with them the nostalgia of what I didn’t even realize I had missed.

These empty hollows, as if lifeless, full of memories that don’t belong to me, let me feel the life that had gone missing from them. I can understand the pain of their absences because I feel the ones that I keep.

That hurt – huh Miguel?–, because the shots seem to be waiting for movement as always. Like when once, voices could be heard there, and your aunts cleaned the hall, cleared up the small garden, lit the fire, and light reflected from the windows. Now, these images reflect this heartrending loneliness that must be felt from some photos taken with such innocence, photos that being so essential, so minimal, are capable of saying so much. These images of an old building, almost in ruins, architecture that looks like it shouldn’t be seen, so as to not disturb, passing through on tiptoes among its phantoms –your phantoms–, these are sentiments that you can’t hide. And you did it well, because it also hurts others. These ghosts are inside all of us who have already experienced some of those unwanted absences.

These photos are made for those who can say they have lived, and not only that they are alive.

I’m not surprised that some triptychs of these images have won the Lux Photographic award.

I’m overwhelmed.

To understand them you have to look, but not just a superficial look, just a glance and that’s that. It is necessary this «seeing» that looks with many more organs than the eyes, that adds heart to feel them, brain to understand them and soul to give them life with our imagination. That way, we don’t only understand the images, but we also understand yourself. You can see Miguel walking through walls of emotions, looking for the essences of what was once there, the remains of that perfume that reminds you of someone you love, and that for you, seems to live in the memory of all the things.

And for those who, like me, know the photographer Miguel well, these photos are also a contradiction.

They are the opposition to the controlling photographer, perfectionist, who sought and sought the lights, who changed focuses and contrasts not once, but over and over again, who shaded, who adjusted, readjusted, composed and recomposed the scene, the still-life’s, the stages…, with a fineness of particular and recognizable style. An authentic manipulator of the elements, a professional who knows what he is doing and uses the resources of his craftsmanship.

And yet here there is nothing of that, of that preparation, of that intervention.

Everything was in place here for you. To change one small detail was to destroy the composition, unstable the scene; worse still: to touch something was to blur the purity of feelings. Everything is exactly what it was, everything is as it was, and you have been nothing more than a witness that nothing had changed. This is pure photography. What is out there and what we capture must correspond in the world of emotions with something that is inside us, nailed intensely, because, without that correspondence, we are as dead as if the images had been captured by a robotic camera in any corner of a city. And that’s not what happens here.

This is alive and talking.

But Miguel, you can’t escape from yourself. In the end, you have fallen into the trap, and you are up to your neck in a process more uncontrollable than not. The 30 x 40 cm camera that I had left you as forgotten in a corner of your studio, the museum piece made in 1840 by Louis Pin on the outskirts of Paris, fourteen years after the birth of photography, has come back to life and has seduced you with its square and categorical curves. You caressed it as if it was an Aladdin’s lamp and it began to give us images of the wet collodion plate process, as if we lived in the past. Perhaps the camera is a sister in the times of the building 101, with whose photos we have been seduced and kidnapped. The ferrotypes fit perfectly between its walls, they complement, decorate and integrate in an unthinkable way with what the rest of the images pretend.

I wonder which of the two ideas came through first, what led to what, who inspired whom.

Anyway, I have to accept that, having fallen into your own trap, has been the perfect touch for an exhibition that was already exceptional, but, with the wet collodion plate samples, it’s the perfect reference.

Unlike the photos of the building, the old ferrotypes took me back in time to the past, to the past of the building and its life, to “its” past. It seems like I can live it in those that were my memories, which are not these. The Virgin in her niche, the old objects, cables, chairs, boxes, and lamps, are to your recently taken photos of the old building, like young images recently taken down… more than a hundred years ago. No, these photos are not a notarial deed, they are not a topographical description of reality, and they are not part of an administrative memory to which they have been stapled.

Like a pencil that is used to write the shopping list, or to write a poem, to draw the dream of the wisest of men, or scribble “mama” for the first time, all these things are also available to whom has learned to use the resources that is concealed within, to express what is hidden in its own feelings and emotions. Baring oneself so much can be frightening, because we show our weaknesses, but when sometimes someone dares to do it, life gives us gifts like this exhibition. Enjoying it is very simple: stop and look.

It’s very good.

Very good.

By Valentin Gonzalez

Translated to English by the great Sandra Crundwell