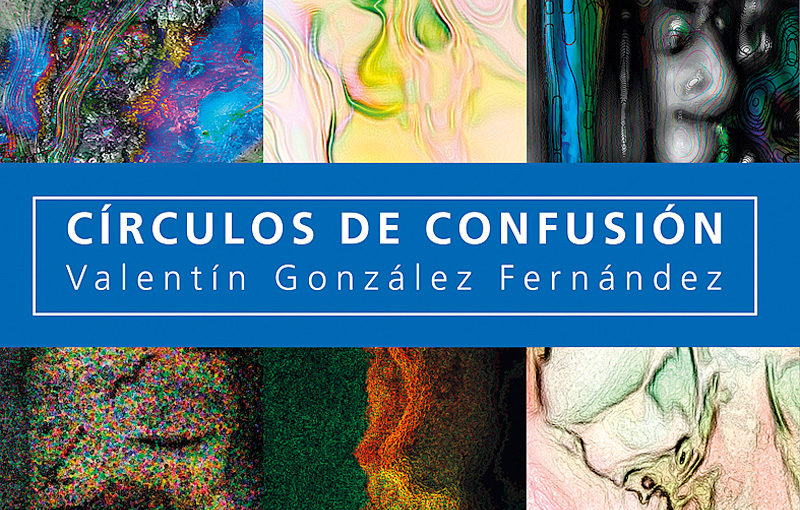

Sobre el libro «CÍRCULOS DE CONFUSIÓN»

About the book “Circles of Confusion”

Entrevista de Pilar Diago a Valentín González sobre su libro “Círculos de Confusión” para COLORAVANZADO

An interview of Pilar Diago to Valentín Gonzalez about his book “Circles of Confusion” for COLORVANZADO

En junio de 2011 le hice una entrevista a Valentín sobre el libro “La Realidad Simultánea”, subtitulado como: “ensayo para la aproximación a otro tipo de fotografía”, que estaba escrito de su puño y letra. El libro, absolutamente carente de imágenes, planteaba un mundo sin objetos reconocibles como base de su trabajo fotográfico y también como una puerta abierta al futuro de nuevas imágenes fotográficas nacidas del mundo interior. Hablaba del uso de objetos no reconocibles en la obra final, pero necesarios como punto de partida en todas sus creaciones; incluso explicaba su forma de aproximarse a esa realidad y el modo en que buscaba sus propios símbolos para dar luz a nuevas obras. Pero la única imagen, y además parcial, estaba en la portada del libro, dentro solo había palabras.

Entonces le pregunté si en el futuro habría un libro sobre sus colecciones, a lo que respondió que no lo sabía, y que en todo caso sería de imágenes pero no de técnica. También aceptó otra entrevista para hablar de ideas –no de técnica–, a cambio de un buen café. Éste parece el momento oportuno para hablar de ambas cosas: colecciones e ideas.

In June of 2011, I did an interview with Valentín on the book “The Simultaneous Reality”, subtitled as: “essay on the approach to another type of photography”, written in his own handwriting. The book, absolutely devoid of images, contemplated a world without recognizable objects as the basis of his photographic work and also as an open door to the future of new photographic images born of the inner world. He spoke of the use of non-recognizable objects in the final work, but necessary as a starting point in all his creations; he even explained his way of approaching this reality and the way in which he searched for his own symbols to shed light on the new works. But the only image, and in addition, partial, was on the cover of the book, inside there were only words.

Then I asked him if there would be another book about his collections in the future, to which he responded that he didn’t know, and that in any case, it will be a book only of photographs but not of technique. I also accepted another interview to talk to him about ideas –not technique–, in exchange for a good coffee. This seemed like the ideal moment for talking about both things: collections and ideas.

Un libro con 326 páginas, de gran formato, con más de 250 obras de 29 de tus colecciones parece el libro definitivo para un autor. ¿Cómo lo ves tú?

Pues viendo tantas obras juntas me cuesta abarcarlo mentalmente. En él se comprime el tiempo necesario para concluir esas 29 colecciones, que fueron más de 25 años. Verlas así reunidas, aunque se hayan seleccionado algo más de la mitad de las obras que contienen las colecciones, es suficiente para ver mi forma de pensar en épocas a las que solo puedo volver con el recuerdo. Para mí como autor de las imágenes es incluso demasiado denso; me toca demasiadas fibras, me veo desnudo y hasta vulnerable. Por otra parte veo un conjunto de obra honesta y sin concesiones, llevada al límite; así que en resumen me gusta. Estoy muy contento con el resultado y agradezco el esfuerzo del editor.

A book with 326 pages, of large format, with more than 250 works out of 29 of your collections seems to be a definitive book for an author. How do you see it?

Well, when I see so many of my works all together, I find it quite hard to take in mentally. In it, the time needed is compressed for these 29 works, which spanned over 25 years to be completed. Seeing them together like this, even if I did select a little over a half of the works in the collection, is enough to see my way of thinking at times to which I can only go back with the memory. For me, as the author of the images, I also find it too dense; it hits too many soft spots, I see myself exposed and even vulnerable. On the other hand, I see the works as honest and without concessions, works taken to the limit; so to sum it up, I like it. I’m very happy with the results and I appreciate the effort of the editor.

¿Cambiarías algo en su diseño?

Miguel Aroca, el diseñador, puso mucho empeño en limitar los textos. En las primeras pruebas valoramos si el libro necesitaba más descansos de lectura entre las imágenes, sin embargo la densidad que yo sentía era más por las propias obras que por la cantidad de páginas seguidas sin texto. Mi obra es de formato bastante grande y al reducir el tamaño esa información se comprime; para liberar esa presión se incluyeron más de cincuenta páginas a sangre con detalles de la obra de la página de enfrente que se mostraba completa. Con esta modificación todos quedamos satisfechos.

Would you change anything in the design?

Miguel Aroca, the designer, paid a lot of attention to limiting texts. In the first tests we evaluated if the book needed more reading breaks between the images, nevertheless, the density that I felt was more to do with the work in itself than in the number of pages that follow without any text at all. The format of my work is quite large, so by reducing the size, the information also becomes reduced; to free this pressure we included more than fifty full bleed pages, where you can see the complete details of the work on the opposite page. This modification satisfied all of us.

¿Qué puedes decirme sobre los textos?

Desde el principio quise apartarme de textos derivados de un punto de vista fotográfico y creo que este objetivo se consiguió. El único fotógrafo que hace un comentario soy yo y mi texto se añadió en las últimas semanas, estando ya con las correcciones.

Los autores de los textos son escritores, filósofos, directores de museos, galerístas, etc. y por lo tanto creativos, pero no fotógrafos. Su aproximación a mi obra hace que yo mismo la vea a través de sus ojos, como si no fuera mía, pero no la diseccionan como a un cadáver: la muestran como si fuera un ser vivo. Han arriesgado en sus comentarios, porque mi obra no es fácil y tiene sus propias referencias, sin embargo sus textos son agudos, penetrantes y reveladores. Estoy encantado con todos ellos, además sus autores fueron siempre cálidos conmigo, lo que les agradezco enormemente, porque cuando me aproximé a ellos para pedirles su colaboración creía firmemente que no me harían caso. Incluso me hicieron comentarios para un mejor entendimiento de mi obra, que fueron los que me llevaron a añadir el texto explicativo sobre una colección y varias páginas más al final, mostrando el punto de partida de unas imágenes junto a la pieza acabada.

What can you tell me about the texts?

From the start, I wanted to get away from texts derived from a photographic point of view, and I think I reached my aim. The only photographer who comments is me, and my texts were added in the last weeks, during my corrections. The authors of the texts are writers, philosophers, museum directors, gallery owners, etc. Thus, they are creative, but they are not photographers. Their approach to my works helps me to see them through their eyes, as if the works weren’t mine, but without dissecting them as if they were corpses: they show them as if they were living beings. They’ve taken a risk with their commentaries because, for one thing, my work is not easy, and for another, it has its own references, nevertheless their texts are sharp, penetrating and revealing. I’m delighted with all of them, besides, their authors were very kind to me, and I thank them enormously because when I approached them to ask for their collaboration I seriously thought they wouldn’t take any notice. They even made comments to me for a better understanding of my work, which were what led me to add the explanatory text on a collection and various pages more at the end, showing the starting point of some of the images together with a finished work piece.

¿Están representadas todas tus colecciones?

No. Faltan dos de las primeras colecciones y los trabajos después de la número 29. Ésta última retrasó la salida del libro porque su inclusión se decidió muy al final. De las dos primeras descartadas una se desarrolló en un formato diferente, pues tenía mucho de experimental o de estudio para lo que vendría después. La otra colección presentaba seis variaciones sobre un mismo tema pero que no podrían representarse en una sola imagen, e incluirlas todas me pareció excesivo, de modo que se quedó fuera.

Are all of your collections represented?

No, two of the first collections, plus the works done after the 29th are missing. This last one delayed the release of the book because we didn’t decide on its incorporation until the end. Of the two discarded, one of them developed in a different format, it had a lot of experimental or study for what was to come. The other collection presented six variations on the same theme, but that couldn’t be represented in one single image, and to include them all seemed excessive, so they were left out.

Como primer impacto visual del libro, tus obras se alejan radicalmente de la estética fotográfica conocida o clásica. ¿Cómo les afecta eso? Por ejemplo en el plano comercial.

Afecta de todas las maneras, por supuesto. Mi obra no es puramente comercial o decorativa porque está lejos de lo normal o conocido. No es fácil de comprender, especialmente cuando saben que es una fotografía, ya que no aceptan o no entienden de dónde sale; sin embargo para otros es genial o único. Bueno, hay opiniones de todos los gustos, pero es algo que tengo muy asimilado y que no me altera demasiado. El éxito económico de la obra no es mi objetivo principal, si lo fuera estaría haciendo otro tipo de fotografía con resultados comerciales contrastados.

En el momento que decides seguir un camino más de “Arte”, sin imposiciones, sin otros compromisos o condicionantes que no sean tú mismo, tus límites y la propia obra, está claro que asumes que la parte comercial queda en cuarto o quinto plano. En mi caso la elección estaba clara, porque cuando se me abrió la puerta o la posibilidad de penetrar en la Realidad Simultánea si decidía continuar, no había ningún referente previo al que acudir. Era aquello de “o tú o nada”. A partir de ahí todo lo que hacía, perseguía o intentaba exigía mi límite personal y técnico; siempre estaba al borde del vacío y esto asusta tanto como engancha.

Exige una estética propia que está prácticamente impuesta por lo que acabas de descubrir, una nueva forma de expresarte, los temas que toco…, en fin, hay una serie de circunstancias que rodean mi obra que no la hacen especialmente comercial. Tal vez resulte muy densa de contenido para los tiempos que corren, que parecen sugerir un arte bastante más superficial.

As the first visual impact of the book, your works radically move away from the known or classical photographic aesthetics. How does that affect them? For example, on the commercial side.

It affects them in all ways, of course. My work is not purely commercial or decorative, the reason being is because it’s far from what is normal or known. It is not easy to understand, especially when they realize it is photography, as they can’t accept or they don’t understand where it comes from; nevertheless, for others, it’s brilliant or unique. Well, there are opinions for all tastes, but it is something that I have accepted and it doesn’t trouble me too much. The economic success of my work is not my main aim, if it was, I would be doing another type of photography with proven commercial results.

The moment you decide to direct your vision more towards “Art”, without impositions, without other commitments or constraints that are not of yourself, your limits and the work itself, becomes clear enough for you to assume that the commercial part remains in a fourth or fifth plane. In my case, the election was clear, because when that door opened up for me, or to put it another way, when I penetrated into the Simultaneous Reality, as long as I decided to continue, there was no other earlier reference for me to turn to. It was “or you or nothing”. From then on everything I did, pursued or tried compelled my personal and technical limit, I was always on the edge of the void and this for me is as scary as it is addictive.

It requires an aesthetic of its very own, one that is practically imposed by what you have just discovered, a new way of expressing, and the topics that I cover…, anyway, there are a series of circumstances that surround my work that doesn’t make it especially commercial. Perhaps it can seem very dense in content for times like these, which seem to suggest a rather superficial art.

¿Tiene eso que ver con las galerías?

Es un conjunto de cosas que sumadas hacen que interese a un público general o a un grupo más reducido, o curioso, o experto, o como se quiera decir.

Las galerías no son instituciones benéficas, viven de vender obras, por lo que dirigen sus intereses a cosas conocidas o ya aceptadas. Pueden arriesgar en una exposición, pero no en cada una. Parecen el ogro del mercado del Arte pero no lo son, ellas también forman parte de ese mercado e igualmente lo sufren.

El mundo del Arte de verdad es impredecible. Salvo en contadas ocasiones entre las que siempre se menciona a Picasso y cuatro más, los autores que hoy cuelgan en las paredes de los museos del planeta han tenido mucha más hambre que triunfos. La lista de los triunfadores del pasado casi coincide exactamente con la de los que eran despreciados en su tiempo. Lo raro es que alguno de los conocidos del pasado sigan siendo los admirados hoy en día; de esto hay muchos, muchos ejemplos, no es solo Van Gogh.

Hay que entender que cuando haces algo nuevo, raro en tu tiempo, no visto en su época, con un público no preparado para ello, incluso despistado por toda la información contradictoria, no puedes esperar que te traten como si fueras el rey del pop. Si no lo tienes asumido debes prepararte para pasar malos ratos porque está cantado lo que probablemente ocurra.

Does this have anything to do with the art galleries?

It is a group of things that together make it interesting to the general public or to a smaller group, or curious, or expert, or however you want to say it.

The galleries are not charitable institutions, selling art is their sustenance, so they direct their interests to things that are known or have already been accepted by the public. They can take a risk in one exhibition, but not in all of them. You may consider them as the ogre of the Art market, but they are not, they also form part of this market as well as suffering it.

The real Art world is unpredictable. Except on a few occasions, between those who are always mentioning Picasso and a few others, the authors that you find hanging on the walls of museums around the world today, had suffered more hunger than triumphs. Almost all the authors from the past who succeed today were despised in their time. The weird thing is that some of the well known of the past continue being admired today; there are many, many examples of this, and it’s not just Van Gogh.

You have to understand that when you do something new, rare or unseen in its time, with an audience not ready for it, even confused for all the contradictory information about Art that they have, you can’t expect them to treat you like the king of pop. If you don’t assume it, prepare yourself to go through a bad time because surely that is what will happen.

A pesar de todo el arte en el mundo virtual e internet ¿sigues considerando necesarias las galerías?

Yo, muy particularmente, creo que mi obra necesita no una galería, sino un galerísta, porque hago algo no visto, fuera de lugar, que necesita ser introducido como lo que es: un camino nuevo. Necesita que se explique personalmente a los clientes el punto de vista de partida, lo no-objetual, su significado, o su importancia, lo que se pretende, para que se destape el mundo que oculta ésta nueva fotografía. Cuando se hace esto el resultado parece mágico.

No digo que se tengan que explicar mis obras, eso es absurdo, porque si no hablan por si solas no hay más que decir de ellas. Pero si estoy presentando un nuevo código, un nuevo lenguaje, otro idioma de expresión y no se entiende este “código-lengua” es como hablar en un idioma desconocido y decir cosas muy hermosas que nadie comprende.

Aunque alguien vea tu obra colgada en una feria y alucine y comprenda lo que ve, o que la estética ilumine a un espectador y se enamore de una foto, el resultado es menor por comparación con lo que ocurre cuando un galerista muestra el fundamento de tu obra con detenimiento a un cliente.

Para mí la figura del galerista es insustituible, nada puede igualar su labor como introducción a una obra, pero… también comen cada día.

In spite of all the art in the virtual world and Internet, do you still consider galleries of art necessary?

Personally, I think my work is not just in need for a gallery, but in need of a gallery owner, because what I do is something never seen before, something out of place, something needing to be introduced as it is: a new path. The starting point of my work, the non-objectual, its meaning, its intention, or its importance needs to be explained personally to the clients so that the world that this new photography hides become visible. When this is done the result seems magical.

I’m not saying that my works must be explained, that is absurd, because if they don’t speak for themselves there would be nothing more to say about them. But, if I am presenting a new code, a new language, a new way of expressing and this “code-language” is not understood, it’s like speaking in an unknown language, saying wonderful things that nobody understands.

Even if somebody sees your work hanging in an Art Fair and becomes amazed by it and comprehends what he sees, or if the aesthetics illuminate the viewer and he falls in love with the photo, the result is less in comparison to what happens when the gallery owner, with utmost care, shows the client the basis of your work. For me, the figure of the gallery owner is irreplaceable, no one can equal his work as an introduction to a work piece, but… they also eat every day.

¿Por qué dejaste de exponer?

Cuando tomé mi camino no-objetual ya sabía de antemano que lo que hacía era para mí y cuatro amigos a mi alrededor, que veían tan asombrados como yo lo que estaba naciendo allí y, conscientemente, dejé de exponer para concentrarme en crear las colecciones que nacieron a partir de ese momento. Sin embargo lo que hacía hasta entonces se vendía bien, así que fue una decisión personal y meditada que nadie comprendió. Pero no podía dedicar mi tiempo a la vez a hacer mi nueva obra y a mostrarla o promocionarla, lo que me llevó a tomar la decisión de parar de exponer y no me arrepiento, no me equivoqué; volvería a hacerlo.

De pronto apareció un galerista, Antonio Pena –que también escribe en el libro–, que descubrió unas obras por casualidad en una visita a mi taller. Había venido varias veces a que le imprimiera pruebas certificadas para museo y yo nunca le había mencionado que tenía obra personal, hasta que en una ocasión preguntó por el autor de unas fotos de paisajes colgadas en la pared que le atrajeron. De pronto vio que eran mías y se sorprendió de que nunca le propusiera exponerlas en su galería, pero más aún le sorprendió que le dijera que no eran Arte. Me preguntó qué era lo que yo consideraba Arte y entonces le enseñé algunas obras de mis colecciones. El se ofreció a llevar mi obra y me aconsejó presentarla a otras galerías e instituciones y así es que he vuelto a exponer, pero sin estar dedicado a la promoción de mi obra. Para mi lo importante es hacerla, el éxito es una cosa humanamente deseable, pero puramente circunstancial. Si la obra es buena y resiste el paso de los años sin deteriorarse su éxito es inevitable. Todo es una cuestión de tiempo, a todo le llega su hora aunque sea cincuenta años después y el autor ya no esté aquí. Por eso este libro me parece importante, porque deja rastro para entender lo que estoy haciendo ahora, más de veinticinco años después de haber encontrado otra vía fotográfica. ¿Quién sabe lo que puede ser necesario en el futuro?

Why did you stop exhibiting?

When I moved on to my non-objectual path I knew beforehand that what I was doing was for myself and a few close friends who were as amazed as I was by what was being born there and, consciously, I stopped exhibiting to concentrate on creating the collections that were born from that moment. Nevertheless, what I did until then was selling well, so it was a personal and meditated decision that nobody understood. But I couldn’t devote my time to my new work while promoting or showing it, which made me decide to stop exhibiting altogether, and I have no regrets in doing so, I was not wrong; I would do it again.

Suddenly, a gallery owner turned up, Antonio Pena –who also writes in the book–, he accidentally discovered some works of mine during a visit to my workplace one day. He had come by several times for me to print out some artists proofs for museums, but I had never mentioned to him before that I had my own personal works, when one day, while observing some photographs of some landscapes hanging on the wall that had attracted him, he asked me who the author was. Suddenly, when he found out they were mine, he thought it strange that I had not asked him to have them shown in his gallery, but his surprise was greater when I told him that I did not consider them Art. He then asked me what was it that I considered Art, and that was when I showed him some works of my collections. He offered to take care of my work and advised me to offer it to other galleries and institutions, so that is how I returned to exhibiting again, but without having to devote myself to the promotional side of my work. What is important to me is doing it, to succeed is something humanly desirable, but purely circumstantial. If the work is good and resists the passage of time without deterioration, its success is inevitable. It’s just a matter of time, and for everything, there is an end, even fifty years on when the author is no longer with us. This is why this book is important to me because it leaves a trail to understand what I’m doing now, more than twenty-five years after having found another photographic path. Who knows what may be necessary for the future?

Es cierto que son colecciones muy particulares y con un concepto fuera del pensamiento fotográfico clásico. ¿Crees que tu obra es única?

Esto suena a: “Cualquier cosa que diga será utilizada en su contra”, como en los juicios. Son mías, totalmente mías desde la técnica empleada al concepto interno que las guía. Llevo décadas haciéndolas y jamás he visto nada parecido; ni en la etapa analógica ni en la digital. Incluso la estética o los temas no tienen nada que ver con lo que se espera del entorno fotográfico, pero quiero hacer una matización: una cosa es que sean únicas y otra es que sean buenas. Para mí lo son, naturalmente, son lo mejor que puedo construir, pero será el tiempo, el futuro, los humanos que vendrán quienes tendrán la capacidad de entender los códigos de hoy en día y valorar lo que hemos hecho en esta época los que les hemos precedido. La cosa es no sentirse avergonzado por nuestras obras respecto a lo mejor del pasado, y aportar algo para el futuro que sólo nosotros podemos hacer: enseñarles lo mejor que tenemos dentro en este momento de la historia. Y que lo usen bien y para bien, desde luego.

It is true that they are special collections with a concept outside the classical photographic thinking. Do you think your work is unique?

That sounds like: “Anything you say will be used against you”, like in the trials. They’re mine, totally mine from the technique used to the inner concept that guides them. I’ve been doing them for decades and I’ve never seen anything like them, nor in my analogical or in my digital stage. Even the aesthetics or the subjects have nothing to do with the photographic background expected, but there is something I would like to clarify: one thing is their uniqueness and the other is whether they are good or not. For me they are, of course, without a doubt they are the best I can do, but only time, the future, and the following generations will be able to understand today’s codes, and have the ability to give value to what has been done in this day and age for those that have preceeded them. The questions is not to feel ashamed by our works with respect to the best of the past, and offer something to the future that only we, ourselves, can do: show them the best that we have inside us at this moment of history. And that they use it well and be for good, of course.

¿Cómo es tu proceso de creación?

Normalmente comienza con algo que me llama la atención. En las primeras colecciones incluso se derivaban de cosas que veía en la anterior y que luego investigaba. Actualmente es más visual, más emocional. Ocurre que algo me hace sentir la necesidad de volver a mirar, de pararme, de dar la vuelta, aunque no sepa qué es. Sé que allí hay algo, pero no tengo por qué encontrarlo inmediatamente. Eso no me preocupa demasiado, no me importa volver más veces para encontrar las referencias que pueden abrirme la puerta y, en ocasiones, esto ha ocurrido años después, incluso muchos años después. Sin embargo no busco una foto, busco una historia, todo un relato que pueda desarrollar. Las cosas poco a poco se van encajando y tomando cuerpo. Evidentemente el proceso es lento, no muestro trabajos a medio concluir, no expongo “ensayos” por así decir, siempre son las “conclusiones”.

Tras visualizar las posibles imágenes, hago unas pruebas para definir la técnica que voy a usar en el “rescate” de los actores del entorno en que están incluidos. Las colecciones suelen tener técnicas diferentes entre ellas y, generalmente, todas las obras de cada colección tienen el mismo proceso. Jamás he vuelto al mismo sitio a disparar dos veces una colección o a añadir disparos; cuando decido las tomas empleo el tiempo preciso para la captura y dejo cerrado ese capítulo.

Verdaderamente todas las partes del proceso tienen la misma importancia, pero lo que dispara el proceso es un nuevo toque de atención sobre algo que acabo de descubrir. Es un momento especial, casi diría que mágico, que te eriza la piel y te mete en un mundo nuevo y fantástico. Sin ese momento no hay nada detrás, por lo que tengo tendencia a pensar que esa es la parte más importante.

How is your creation process?

I usually start with something that catches my attention. In the first collections they even came from things I saw in the previous one and then investigated. Nowadays, it’s more visual, more emotional. Something happens around me that makes me feel the need to look again, to stop, to turn around, even if I don’t know what it is. I know something is there, but I don’t have to find it immediately, that doesn’t worry me too much, I don’t mind having to return again and again to find the references I need to open that door and, sometimes when this happens, an entire year has gone by, or even many. However, it’s not a search for the photo, it’s a search for a story, a whole tale I can develop. Little by little everything fits together and takes its shape. Evidently, this process is slow, I don’t show my works half-finished, I don’t exhibit “rehearsals” so to speak, they are always the “conclusions”. After viewing the possible images, I do some tests to decide which technique I’m going to use during the “rescue” of the actors included in the surroundings. Usually the collections have different techniques among them and, generally, all the works of each collection go through the same process. I’ve never gone back to the same place twice to capture a collection, neither have I gone back to add new captures to it. When I decide the camera shots, I use the precise time I need for the capture and then leave that chapter closed.

To tell you the truth, every part of the process has the same importance, but what triggers this process is a new call for attention to something I’d just discovered. It’s a special moment, almost magical, enough to give you goose bumps, it draws you into a new and fantastic world. Without that moment there is nothing behind, so I tend to think this is the most important part.

¿Qué te inspira del mundo real?

La inspiración es lo que me hace encontrar el tema. Mis influencias, mi mundo, mi vida…, son los responsables de que en determinado momento mi inconsciente me dé un toque de atención sobre algo a mi alrededor. De ello se derivan ideas que, una vez comenzado el proceso artesano, generan nuevas ideas, estéticas, modos de expresión, roturas de las normas académicas, antagonismos, etc. La inspiración está en la vida y el mundo en que vivo. Nada sería igual hace un siglo o dentro de un siglo. Aunque sean imágenes extrañas están contando algo que, de este modo, sólo las podría generar en mi época.

What inspires you in the real world?

It´s the inspiration that helps me find the subject. My influences, my world, my life…, are responsible that at certain moments in my subconscious I get another call for attention on something that’s around me. This is where I get my ideas from once the artesian process has begun; generating new ideas, new aesthetics, new forms of expression, the breaking of the academic rules, antagonisms, etc. Inspiration is in the world I live in. Nothing was the same a century ago, nor will it be a century from now. Although they are strange images they are telling us something that, thereby, I could only create in my time.

¿Qué quieres enseñar con tus fotografías?

La pregunta es muy exacta, porque no es lo que quiero contar, no cuento historias, no las escribo, las “enseño” en un relato lleno de huecos, de vacíos conscientes, que obligan al observador a rellenarlos con su propia intuición. Fuerzo a que quien las mira con detenimiento, se enfrente a sí mismo como en un espejo interior y encuentre lo que quiere, o puede, sentir en cada momento. Si fuera un libro, estaría lleno de huecos en las frases que el propio lector debería rellenar, y en las que puede decidir si quiere amar u odiar, por ejemplo. Hago que se pregunte sobre el qué, el por qué, el cómo, el cuándo…, de lo que allí está ocurriendo. Hago que saque su propio sentimiento para que se una a mí, y por supuesto a todos los demás. Todos somos iguales internamente, las diferencias están prefabricadas. Ocurre frecuentemente que dos personas que entran juntas a una exposición de mi obra ven cosas diferentes en ellas, incluso radicalmente diferentes. Hay otros mundos visibles a través del sistema fotográfico, puede que estén dentro de mí y haya encontrado un camino para mostrarlos. La intención final es, evidentemente, que los espectadores los encuentren a través de mi obra y puedan disfrutarlos. Es como un golpe de consciencia.

What do you want to show with your photographs?

The question is very exact because it’s not about what I want to tell, I don’t tell stories, I don’t write them, I “show” them in a story full of gaps, of conscious voids, which obliges the viewer to fill them in with their own intuition. I force those who look at them thoroughly, to face themselves as in a mirror from within and find what they want, or can, feel at every moment. If it was a book, there would be many gaps in the phrases that the reader himself would have to fill in, and in which he could decide if he wants to love or hate it. I make the reader ask about what and why and how and when…, of what is happening there. I draw out his feelings, for me, and of course for all the others. We are all the same internally, the differences are pre-fabricated. What happens often is that two people who go together to see one of my exhibitions, see different things in them, including radically different things. There are other visible worlds to see through the photographic system, it could be that they are inside me and I have found a way of showing them. The last intention is, evidently, that the spectators find these worlds through my work and can enjoy them. It’s like a coup of awareness.

¿Qué sientes cuando ves aparecer a los personajes de tu obra?

Yo intuyo cómo pueden ser, pero no lo sé a ciencia cierta hasta que con las pruebas que hago se plantan ante mis ojos. De modo que no es algo exacto desde el primer momento. Esto quiere decir que también son una sorpresa para mí mismo. Es muy emocionante, por supuesto.

What do you feel when one of your characters appear in your work?

I intuit how they can be, but I don’t know for sure what will they look like, until the tests are done. So it’s not exactly clear from the first moment. That means that it is also a surprise to me. It’s very thrilling, of course.

¿Crees que es eso lo que hay en el fondo de tu subconsciente?

No lo sé, pero cuando hago una obra tengo la sensación de que era así desde siempre, y que la acabo de rescatar de otra parte, llámese mundo o dimensión; por eso lo de “Realidad Simultánea”. Es decir, ya me era conocida de algún modo, es como un “deja vu”. Evidentemente es mía y soy yo, por lo que la sorpresa está más en su belleza que en su existencia. Es como ver el rostro de un hijo recién nacido: es él y le hemos puesto cara, nada más y nada menos, pero en el fondo sabíamos que existía.

Do you believe that this is what is at the bottom of your subconscious?

I can’t tell, but when I do a work piece I feel that it has always been that way, and that I have just rescued it from somewhere else, call it world or dimension, that’s the reason of “Simultaneous Reality”. I mean, it was already known to me in some way or another, it’s like a “déjà vu”. It’s obviously mine and it’s me, so the surprise is more in the beauty than in its existence. It’s like seeing the face of a newborn: it’s him and we’ve given it a face, nothing more and nothing less, but deep down we knew it existed.

En las últimas hojas aparece la captura original junto a la obra acabada, lo que me parece sorprendente sabiendo lo que te molesta responder a “¿cómo lo haces?”. ¿Es para demostrar que salen de la realidad?

No, pero forma parte de la idea de que se debe explicar el concepto de este “nuevo mundo”, porque así se abren los ojos del espectador.

Ferrán Olucha, que tiene un precioso artículo en el libro, no se ha cansado de repetirme en los últimos años –especialmente desde que vio la obra que iba a exponer en el museo que dirige–, que debería explicar siempre el origen de mi obra, porque eso la divide en un antes –el mundo real–, y un después –la “Realidad Simultánea”– lo que facilita mucho al espectador la comprensión de lo que ve realmente.

On the last sheets of paper, you can see the original capture next to the finished work, I find this surprising when I know how it bothers you having to answer the question to “how do you do it?” Is it to prove that they come out of reality?

No. But they do form part of the idea that the concept of this “new world” must be explained because this is how the viewer’s eyes open up to it.

Ferran Olucha, who’s written a lovely article in the book, has never tired repeating it to me in recent years –especially since he saw the works that I was going to show in his museum, he says that the origin of my work must always be explained, because this divides into a before –the real world–, and an after –the “Simultaneous Reality”–, which helps the viewer comprehend what he is really looking at.

Después de ver los cientos de imágenes de tu libro me pregunto si esto es de verdad lo que ves cuando miras a tu alrededor.

Me acabas de traer a la cabeza una graciosa anécdota que me contó Justo Serna hace unos días mientras comentábamos sobre el libro: a un escritor muy conocido le preguntó un entusiasmado admirador que le tropezó por la calle si él era el Sr. X, a lo que el escritor le respondió que “a veces sí, pero no todo el tiempo”. Déjame responderte lo mismo y de paso le agradezco a Justo la preciosa introducción que me preparó para el libro.

After going through the hundreds of photographs of your book I ask myself if this is really what you see when you look around you.

You’ve just brought to mind a funny anecdote that Justo Serna told me a few days ago while we were commenting the book: An enthusiastic admirer who bumped into another well-known writer on the street, asked him if he was Mr X, to which the writer responded: “sometimes yes, but not all the time”. Let me answer you the same way, and whilst doing so I’d like to thank Justo for the lovely introduction he did for the book.

Visualmente el conjunto de la obra parece muy metafísico, incluso por los propios títulos, pero no parece anclado en la sociedad actual.

Es que no lo está. El día a día es algo que no me estimula como tema para la obra, al menos no como su fundamento. La misma sociedad se preocupa en conjunto de todo lo que le afecta y de hacerlo notorio hasta la saciedad aunque no lo resuelva. La crítica sobre tanto ruido no deja de añadir más ruido al tema, especialmente porque si no se cambian las cosas es porque en conjunto no se quiere hacer lo necesario. Yo creo que los humanos tenemos claro lo que queremos y lo que no queremos; otra cosa es que nos hayan borrado lo que es fundamental en nuestra existencia o difuminen nuestras aspiraciones con tanto exceso de información interesada, pero todo esto ya lo sabemos y no me parece necesario echar más agua al mar para saber que es un mar. Me interesa más penetrar en otros mundos, por utópicos que sean, porque pueden ser tan hermosos, fantásticos e imaginativos como quiera. Sin embargo creo que el mundo físico se retrata de alguna manera en mi obra, porque no puedo escapar a la influencia de todo lo que me rodea y de mis propias circunstancias, pero a la hora de contar mis historias prefiero que sean de mi vida interior; no discutiré si es real o irreal, pero al menos no es una perversión de la verdad.

Visually, as a whole, the work seems very metaphysical, even by the titles, but it doesn’t seem stuck in today’s society.

Because it isn´t. The day to day is something that does not stimulate me as a subject for my work, at least not as it´s foundation. The same society as a whole worries about what affects it, and makes it notorious until they are blue in the face, even though they don´t solve it.

The criticism about all the noise only adds more noise on to the subject, especially because, if things are not changed the reason is, generally, that they don’t want to do what’s necessary. I think we humans have it clear about what we want and what we don’t want; another thing is that they’ve wiped out what is fundamental to our existence, or that they dilute our aspirations with an overload of surplus information, but we already know this so I don’t think it’s necessary to add more water to the ocean to know that it is an ocean. I’m more interested in penetrating other worlds, no matter how utopian, they can be so beautiful, fantastic and imaginative as you desire. Nevertheless, I think the physical world is somehow portrayed in my work, because I can’t escape from the influences of everything that surrounds me and my own circumstances, but when it comes to relating my stories I prefer that they be from my interior life; I won’t discuss if it is real or unreal, but at least it’s not a perversion of the truth.

Y ¿cómo es ese mundo utópico del que partes?

Supongo que cada colección muestra un mundo interior diferente, como separado por alguna extraña dimensión. Pero como norma es un mundo unido y único, sin fronteras, con gente que se siente igual a los demás en lo esencial. Parto de la idea de que todos somos el mismo ser visto bajo diferentes circunstancias, como una variación del mismo tema. Todos somos –maravillosamente– polvo de estrellas, en esencia como el asfalto que pisamos, pero aunque somos materia consciente, somos muy poco transcendentes para creernos tan importantes. Lo que hacemos hoy, por importante que pueda parecer, si lo vemos con la perspectiva de diez mil años parece que se multiplica por cero. La tierra es un diminuto punto en la galaxia, es nada en el universo, ¿hasta qué punto podemos ver nuestros actos o creaciones como transcendentales? En mi opinión es necesario inundarse de sencillez antes de crear nada que merezca la pena. Yo particularmente me siento inferior a mi propia obra, aunque sé que esto les ocurre a muchos creadores. Procuro que los mundos de mis colecciones estén llenos de luz y humor. Crearlos es un proceso emocionante y agotador, pero difícilmente lo cambiaría por otra cosa. Lo que me aturde del libro es que parece más “yo” que si fuera un retrato.

And, how is this utopian world you part from?

I suppose each collection shows an inner world that’s different, as if it’s separated by some strange dimension. But as a rule, it’s a united and unique world, without borders, where people feel equal to others in what is essential. I start from the idea that we are all the same beings seen from different circumstances, as a variation of the same subject. We are all –wonderfully–stardust, essentially like the pavement we tread on, but even though we are conscious matter, we are not transcendental enough to believe we are that important. What we do today, as important as it may seem, if with the prospect of ten thousand years it seems to multiply by zero. The earth is just a speck in our galaxy, it’s nothing in our universe, so, to what extent can we see our actions or creations as transcendental? In my opinion, it’s necessary to inundate ourselves with simplicity before creating anything that’s worthy. I particularly feel inferior to my work, although I know this happens to many creators. I make sure that the worlds in my creations are full of life and humour. Creating them is an exciting process and very tiring, but I don’t think I would change it for anything else. What disturbs me about the book is that it seems more “me” than if it were a portrait.

La colección Dodecatónicos, que es la que abre el libro es también la que ha provocado el retraso de la edición. ¿Está basada en alguna música concreta? ¿Qué puedes decirnos de ella?

Lo que me inspiró la colección fue descubrir en las paredes de una cantera abandonada lo que consideré un pentagrama. No fui allí con ninguna idea predeterminada, ni tampoco buscaba imágenes para un tema que tuviera ya en mi cabeza, diría que fueron las propias paredes las que propusieron el tema. Una vez que llené los ojos de aquella musicalidad, los actores aparecieron por todas partes, así que tomé nota cuidadosamente de las posibilidades y todo encajó cómodamente con el Dodecafonismo, la música que rompió moldes a principios del siglo XX de la mano de Arnold Schoemberg, de modo que preparé un guión relacionado con el tema. En la música dodecafónica dan el mismo valor a los doce tonos, lo que me aportó la idea del nombre de la colección al usar la palabra “tono” como un componente del color. De ahí a llamarla “Dodecatónicos” el camino es muy evidente.

Relacionarla luego con La canción de la tierra de Mahler, es casi un juego de palabras, ya que está escrita en las paredes de una cantera. El Pierrot de Schoemberg parecía estar esculpido en la roca para que llegara yo y lo encontrara. La verdad es que con un mínimo de cultura musical la colección se vuelve familiar. En mi caso soy melómano desde muy joven, escucho mucha música y esas obras forman parte normal de mi vida. De no ser fotógrafo, seguramente me habría dedicado a la composición musical; es algo que me transporta a otro lugar.

Entiendo que la música es uno de los grandes inventos de la humanidad y, como Arte, posiblemente sea el más grande de todos, pero yo he descubierto con mis fotografías no-objetivas un instrumento capaz de reproducir partes del alma humana y, cuando consigo hacerlo sonar, la música también le sirve de acompañamiento y adorno para tener una experiencia sublime. Mezclar ambos mundos me ha resultado especialmente agradable.

La decisión de esperar a concluir la colección e incluirla, se tomó debido a la extraña circunstancia que se da en ella de que permita que se vea la textura que la soporta. Eso es algo que he ocultado desde el comienzo de mi búsqueda –allá por 1991–, y en realidad casi era el objetivo principal de las primeras investigaciones.

The collection Dodecatónicos, the one that opens the book, is also the one that has provoked the delay of the edition. Is it based on some particular music? What can you tell us about it?

Well, what inspired the collection was the discovering of what I considered a stave on the walls of an abandoned quarry. I didn’t go there with any pre-determined idea, neither did I go to look for images for a subject that I already had in my head, I’d say that they were the walls themselves that proposed the subject to me. Once I filled my eyes with that musicality, the actors appeared everywhere, so I carefully took notes of all the possibilities and everything seemed to fit in comfortably with the Dodecaphonism, the music that broke moulds at the beginning of the twentieth century thanks to Arnold Shoemberg. So then I prepared a script related to the subject. The dodecaphonic music gives the same value to the twelve “tones”, which gave me the idea to name the collection using the word “tone” as, also, a component of the colours. From there, to call it “Dodecatónicos” the path is evident. Then relate it with The song of the earth by Mahler, is almost a play on words, since it’s written on the walls of a quarry. The Pierrot of Shoemberg seems to be sculptured on the wall waiting for me to find it. The truth is that with a minimal musical culture the collection becomes familiar. In my case I have been a music lover since I was very young, I listen to a lot of music and these musical works form part of my everyday life. If I hadn’t been a photographer, I would have certainly dedicated my life to composing music; something that transports me to another place.

I understand that music is one of humanity’s greatest inventions and, as Art, possibly is one of the greatest of all, but I’ve found through my non-objectual photographs an instrument capable of reproducing parts of the human soul, and when I make it sound, then the music also serves as an accompaniment and as an adornment that leads me to a sublime experience. To mix both worlds has been particularly pleasant for me.

The decision to wait to complete the collection and include it was taken due to the strange circumstance that occurs in, that allows to see the texture that it supports. This is something that I have concealed since the very start of my search –back in 1991–, and really, it was almost the main object of the first investigations.

¿Por qué te parece tan importante ocultar la presencia del objeto usado?

Para expresar un concepto es mejor que no haya objetos, porque el objeto es un concepto en sí mismo, y es difícil utilizar cosas que ya son conceptos, o que significan un concepto, para expresar algo diferente a lo que ellos mismos representan. Así que anulando el objeto consigues expresar realmente, de verdad, conceptos puros en sí mismos; consigues mostrar la expresión pura de lo que pretendes sin intermediarios molestos. Acaba de sonarme como si hubiera hecho un juego de palabras, pero es la realidad de mi experiencia.

Why do you think that concealing the presence of the object used is so important?

To express a concept, it is better that there are no objects, because the object is a concept in itself, and it’s difficult to use things that are already concepts, or meaning a concept, to express something different to what they represent. So, by getting rid of the object you can really express the truth, pure concepts in themselves; that just sounded as if I’d made a play on words, but it’s the reality of my experience.

¿Qué aporta la fotografía no objetual o el Fotosimbolismo al Arte fotográfico? ¿Puedes poner un ejemplo real en la práctica?

Hay más de un motivo que justifica la eliminación del objeto reconocible en fotografía, no se trata solamente de producir imágenes con una apariencia extraña. Desde el principio de mi búsqueda pretendía que la obra personal que producía no estuviera limitada por la interpretación de un “actor” –entendiendo por actor un modelo o un objeto–, y eliminarlos era la única forma de atravesar la barrera que separaba al observador de lo esencial que la imagen buscaba en su interior. Pienso que las sensaciones internas están limitadas por la expresividad de los propios objetos o modelos que actúan en la obra.

Es como la expresión facial de los “buenos” y los “malos” en las primeras películas en blanco y negro, que pretenden hacer que el observador sepa desde el principio quién es el bueno y el malo simplemente por las caras que ponen, y utilizan su expresión más y más teatral para señalar un cambio de intensidad en lo moral de sus propósitos. Todo ello es muy cómico e infantil; una interpretación demasiado evidente en la que el análisis de lo que vemos es exactamente lo que representa: buenos y malos. Un cliché en el que casi cualquier otro factor se pierde: interpretamos lo que vemos pero no tenemos necesidad de buscar en nosotros mismos nada más, porque la propia escena se interpreta a sí misma, nosotros no somos necesarios.

Por poner un ejemplo actual muy sencillo, en una fotografía de una figura femenina mirando una flor o un bebé, la escena limita la captura de las emociones a lo que la propia escena y la propia persona incluida –esa concretamente– son capaces de representar por sí mismas. De modo que la emoción del espectador no es libre para interpretar totalmente el hecho de que un ser humano contemple a un bebé o a una flor según su propia sensibilidad interior, sino en función de lo que le transmite concretamente el gesto de la persona que actúa como traductora de lo que yo pretendo expresar. Nada ni nadie, ningún gesto es capaz de mostrar lo que yo siento al observar un bebé o una flor, porque eso es simplemente imposible. Suelo decir que los objetos, o seres vivos, tienen mucha personalidad y que, si quiero mostrar la mía completamente, deben desaparecer físicamente de las imágenes, porque usarlos es como utilizar una máscara trágica.

También ocurre con la fotografía que la personalidad del retratado justifica la imagen, pero no al revés. Es inevitable que los espectadores se acerquen a ver los rostros presentes en las obras, tal vez buscando reconocerlos, pero al mismo tiempo restando importancia al conjunto de la obra que es donde está realmente representada la emoción que busco. Pienso que la representación simbólica, sin objetos reconocibles, obliga al espectador a extraer de su interior la sensibilidad necesaria para hacer suya la obra, y al partir de esta necesidad el artista es capaz de añadir y buscar otro tipo de sensaciones para hacerla más intensa y profunda. Todo ello convierte a la obra como en un espejo en el que el observador se ve reflejado intensamente.

Pero hacer desaparecer el objeto fotográficamente no es algo tan fácil. Para eliminar los objetos es necesario buscar en ellos símbolos que sean interpretables para crear nuevas imágenes con las que expresarse, lo que exige una diferente forma de aproximación visual a lo que nos rodea. Debe entenderse que esta conversión en símbolos de lo que nos rodea no es un simple juego, ni un “a ver qué pasa” usando filtros de cualquier programa de diseño gráfico o una alteración de un proceso químico. Es bastante más complejo, serio y metódico que eso.

Con las imágenes no objetuales la medida de lo que expreso simbólicamente es interna, personal, única y diferenciada de la de cualquier otro ser humano. Con la fotografía tradicional y objetual esa medida es externa y se usa como patrón idéntico para todos, por lo que visto desde el lado del simbolismo y todas las posibilidades que abre, ahora casi me parecería una aberración continuar expresándome de forma tan limitada.

Esa libertad es lo que representa para mi el código de lo no objetual o el Fotosimbolismo.

What does non-objectual photography or Photosymbolism contribute to photographic art? Can you give me a real exampe?

There is more than one motive that can justify the elimination of the recognizable object in photography, it’s not just about producing images with strange appearances. Right from the very start of my search, my intention was that the personal work I produced wasn’t limited by the “actor’s” interpretation –understanding actor as the model or object–, and eliminating them was the only way of crossing the barrier that separated the observer from the essential feeling that the image itself was searching for in its interior. I think that the expresivity of the objects themselves, or of the models that act in the work, limit the internal feelings of the observer.

It’s like the facial expression of “the goodies” and “the badies” used in the first movies in black and white. The intention of it was for the viewer to know from the beginning of the movie who the “goodies” or the “badies” were by the expressions on their faces. By having the actors put on a more theatrical expression when needed to point out a change in the intensity of the principle of their proposal. It’s all very comical and childish; an interpretation that’s too evident in which the analysis of what we see is exactly what is represented: the good or the bad. A cliché in which any other factor is lost: we interpret what we see, but we don’t need to look inside ourselves, because the scene interprets itself, we ourselves are not necessary.

I’ll give you a very simple example, in a photograph where a feminine figure is looking at a flower or a baby, the scene limits the capture of the emotions to what the scene itself and the person included are capable of representing all by themselves. So, the viewer’s emotions are not really free to interpret the fact that a human being is contemplating a baby or a flower according to his own inner sensibility, but of what the particular person’s gesture, who acts as a translator, transmits exactly what I want to express. Nobody or nothing, nor any gesture is capable of showing how I feel when looking at a baby or a flower, because this is simply impossible. I usually say that the objects, or living beings, have enormous personalities and that, if I want to show mine completely, they must disappear physically from the images, because using them is comparable to using a tragic mask.

It also occurs with photography that the portrayed person’s personality can justify the image, but not vice versa. You can’t avoid the viewers from moving close enough to it to see the faces in the photograph, maybe trying to recognise them, but at the same time minimising the work’s importance as a whole, which is where the emotion that I was looking for is really represented. I think that the symbolic representation, void of recognizable objects, obliges the viewer to extract from his interior the sensibility necessary for making the work his very own, and from this necessity the artist is capable of adding to it, and to look for, other kinds of sensations to make it more intense and profound. All this converts the work to a mirror into which the viewer sees himself reflected intensely.

But to make the object disappear photographically is not that easy. To eliminate objects you have to look for interpretable symbols in them to create new images in which to express yourself, and that demands a different way of approaching visually to what surrounds us. It must be understood that this conversion into symbols of what surrounds us is not an easy game, nor a “let’s see what happens” by using filters of graphic designing programs or an alteration of a chemical process. It’s much more complex, serious and methodical than that.

With the non-objectual images the measure of what I express symbolically is internal, personal, unique and differentiated from that of any other human being. With traditional photography, and objectual, this measure is external and is used as a pattern which is the same for everybody, so, seen from the side of symbolism and with all the possibilities that it opens, it would seem now an aberration to continue expressing myself in such a simple way.

This freedom is what represents for me the code for the non-objectual or the Photosymbolism.

Entonces ¿es necesario interpretar un código?

Para poder entender y apreciar una obra debe tener un código, un sistema, un lenguaje incrustado, o será imposible admirarla y será sentida como una casualidad, un experimento y puramente circunstancial.

El lenguaje particular de cada modo creativo tiene sus propios símbolos, las palabras llevan a otras palabras, las formas a otras formas. Cuando se usan las herramientas propias de cada estructura de creación, ella misma abre puertas que de otra manera permanecerían cerradas, y a través de esas formas descubrimos mundos con los que jamás habríamos soñado.

Then, is it necessary to interpret a code?

To be able to understand and interpret a workpiece, it must have a code, a system, an embedded language, or it would be impossible to admire it and it will be felt as if it was a mere coincidence, an experiment and something circumstantial. The particular language of each creative way has its own symbols, words take you to other words, forms to other forms. When you use the tools of each creation structure, it opens doors that would otherwise remain closed, and through these ways, a world to which we would never have dreamed of is unveiled.

¿Hay más colecciones terminadas tras el libro?

Sí, a finales de diciembre 2017 terminé la colección número 30, que lleva por título “Los Vacíos” y está compuesta por 18 fotografías.

Are there more completed collections after the book?

Yes, at the end of December of 2017 I concluded collection number 30, titled “Los Vacios”, a collection composed of 18 photographs.

¿Puedes adelantarnos algún apunte de la colección?

Presenta una estética bien diferenciada respecto a las demás colecciones y un importante salto en la continuidad con la anterior que me resultó muy estimulante. Tiene una particularidad en una de las obras y es que por primera vez en toda mi Realidad Simultánea una de las fotografías se aparta del tamaño cuadrado. La titulada “O uno o nada” tiene un metro por dos de lado; no hubo forma de cortarla en cuadrado y es tan interesante que decidí dejarla en esa medida y seguir trabajándola así.

La colección trata el tema de la relación entre seres idénticos, que viven en el mismo lugar, en un pequeño mundo perdido en un rincón de la existencia, pero que no se reconocen entre ellos como iguales, como hermanos, que no creen tener la misma esencia vital, el mismo corazón, el mismo universo. Todo parece normal superficialmente aunque alterado por dentro, pero bajo el grito de sus gargantas se puede sentir el llanto del vacío de sus corazones. La colección comienza cuando se preguntan quién les ha robado su mundo, partido en divisiones fantasmas y, claro está, terminan encontrando las respuestas, que son esas dieciocho obras que conforman el trabajo.

Can you advance us a little outline of the collection?

It presents a much-differentiated aesthetic with respect to the rest of the collections and an important leap which continued from the one before that I found very stimulating. There is a particularity in one of the works which for the very first time in my Simultaneous Reality, one of the photographs separates itself from the square size. The one titled “Or one or nothing” is one meter high by two meters wide; there was no way it could be cut to a square, and it’s so interesting that I decided to leave it that size and continue working like that.

The collection talks about the relation between identical beings living in the same place, in a small lost world in a corner of the existence, but among themselves they don´t recognice each other as equals, as brothers, and that do not think they have the same vital essence, same heart, same universe. Everything seems superficially normal although altered inside, but under the desperate cry coming out from their throats you can actually feel the weeping of the emptines of their hearts. The collection began when they ask themselves who stole their world, a world cut into phantom divisions, and, of course, they end up finding the answers, which compiles the eighteen photographs that this work is made of.

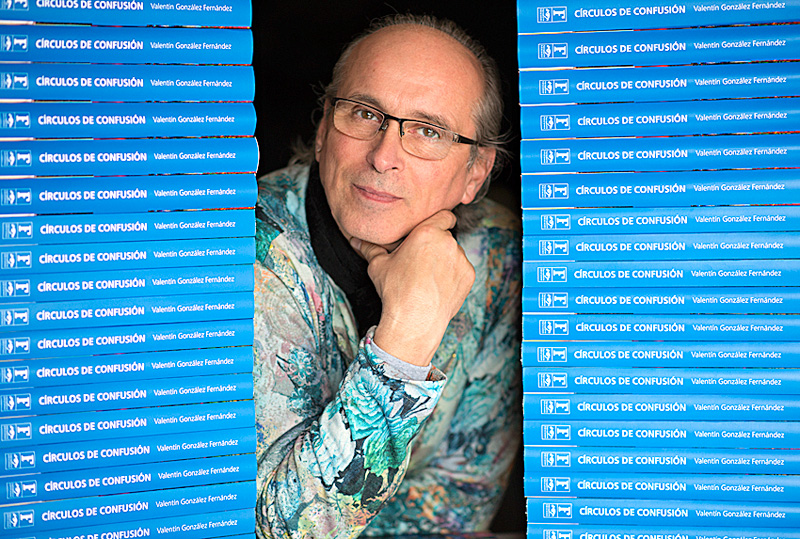

¿Hay más libros tuyos en el horizonte?

Pues sí. Muy pronto sale “Los Yoes”, que forma parte de la colección de doce libros que la editorial está haciendo sobre mis colecciones individualmente. Es el tercero de la colección y ya están empezando a montar el cuarto. Visto el éxito de “Círculos de Confusión” el editor insinuó la posibilidad de producir “Un mar idílico”, el famoso libro de paisajes con la colección que nunca numeré, lo cual a más de uno le sorprenderá; pero no negaré que me gustaría verlo como fue planteado originalmente el trabajo: para ser editado en un libro.

Will there be more books of yours in the future?

Well, yes. “The Yoes” will be coming out soon, this is part of the collection of twelve books that the editorial is doing about my collections individually. This is the third one of said collection and they have already started putting together the fourth. Given the success of “Circles of Confusion” the editor hinted on the possibility of producing “An idyllic sea”, the famous book of landscapes with the collection I never numbered, a collection that will surprise more than one; but I won’t deny that I would like to see it as the work was originally thought of thought of… to be edited into a book.

Tendremos que hacer otra entrevista para hablar de la colección de doce libros…

Con un buen café por medio aceptaré encantado, y si añades unas pastas…

We’re going to need another interview to talk about the collection of twelve books.

For a good coffee, I’ll be only too pleased to accept, and if you add some tasty pastries…

Translated to English by Sandra Crundwell (Sandra, thanks for an incredible translation!)