Soy fotógrafo porque no puedo / I’m a photographer because I can´t be

Nací con casi seis dioptrías de hipermetropía y astigmatismo en cada ojo, pero yo no lo sabía y por lo que parece mis ojos tampoco, porque con tres años parece ser que ya leía. Pero a los cinco años las gafas que llevaba pesaban más que mi cabeza. Los ojos aparecían detrás de medio metro de cristal como dos huevos asustados; yo también me asustaba cuando me encontraba en el espejo, y odié y renegué de aquellos trastos que me avergonzaban cada vez que con diez o doce años me cruzaba con la mujer de mi vida. Opté por quitármelas por la calle, con lo que la mujer de mi vida simplemente desapareció, porque no la volví a ver.

I was born with almost six hyperopia dioptres and astigmatism in each eye, but I was unaware of it, and I can tell you my eyes didn’t know it either, because I started reading at three, so I was told. At five the glasses I was made to wear weighed more than my head. My eyes seemed to peep out from behind a half a meter of magnifying glass like the eyes of a large startled squid, I even startled myself when I saw my face reflected in the mirror, and when i was about ten or twelve I rejected and hated those bulky objects on my little face, they embarrassed me every time the love of my life crossed in front of me. I chose to take them off when I was on the street, with which the woman of my life simply disappeared, because I didn’t see her again.

Mis ojos muy secos, como los de un buen hipermétrope que se precie, no admitían lentillas –dos desgarrones en la cornea lo atestiguan–, así que había que seguir con vasos en los ojos.

My very dry eyes, like those of a good self-respecting farsighted being, rejected contact lenses –two tears in the cornea proved it–, so I had to continue with the coke-bottle glasses over my eyes.

Los cuadros de Philip Barlow tienen mejores ojos que yo. Yo era un inútil, no me quisieron ni para hacer la mili. Cuando en el cuartel, tras dilatarme las pupilas, me quitaron las gafas para averiguar lo que veía me cuadré frente al perchero y me mandaron para casa.

Philip Barlow’s paintings have better eyes than me. I was useless, I mean, they even rejected me when I had to do my obligatory military service. When in the barracks, after my pupils dilated, they took off my glasses to find out what I saw, I stood to attention in front of the coat rack and they sent me home.

Así descubrí mi vocación: No vamos a ponernos las cosas fáciles a pesar de las dificultades. ¡Quiero ser fotógrafo!

Soy fotógrafo porque puedo a pesar de ser un inútil. Y puedo gracias a ese cacharrito que coloco sobre la nariz sujeto por las orejas –objeto exadaptativo, lo llaman–.

De no existir ese aparato que tanto odié, mi imaginación se queda sin capacidad para descifrar lo que habría sido de mi vida. Hay millones de personas que valimos para algo gracias a que alguien tuvo la idea de enganchar dos cristales con un clavo.

That’s when I discovered my vocation: things are not going to be made easier, that I knew, but despite the difficulties, I want to be a photographer!

I’m a photographer because I can be in spite of being useless. And I can thanks to this little gadget I place on my nose and kept in place behind my ears – ex adaptive object, they call it–.

If this apparatus that I hate so much didn’t exist, my imagination would be left without the capacity to decipher what would have become of my life. There are millions of us who are worth something thanks to the person who had the brilliant idea of hooking two lenses together with a pin.

Si yo puedo hacer algo con mi vida se lo debo, especialmente, a Alejandro della Spina, o sería un minusválido, y realmente sin gafas eso es lo que somos muchos de nosotros. Este señor fue un monje allá por el año 1300, que comenzó a fabricar el dichoso instrumento ocular para él y sus amigos, dejando constancia de su invento.

En estos setecientos años es imposible calcular la cantidad de personas que han sido útiles a los demás gracias a su idea. Gracias a nuestras gafas no solo hacemos fotos, también las vemos; y vemos un paisaje, un amanecer, la piel del ser amado, el rostro de un hijo, una obra de arte, leemos a Hesse e incluso vemos la tele.

Ahora mira a ver si en tu pueblo o ciudad hay una estatua, o una calle, dedicada a este benefactor de la humanidad. Apuesto que no la encontrarás.

If I was able to do something with my life, I owe it, especially, to Alejandro della Spina, otherwise I would have become a handicapped individual, and really without glasses this is how many of us are. This person was a monk way back in the year 1300, who started to manufacture this blessed ocular instrument for him and his friends, leaving evidence of his invention.

In these seven hundred years, it is impossible to calculate the number of people who have been useful to others thanks to this monk’s idea. Thanks to our glasses we don’t just take photos, we also see them; we see a landscape, we see daybreak, the flesh of our loved one, the face of a child, a work of art, we read Hesse, and we even watch the tele.

Now go and see if there is a statue in your town or village, or in a street, dedicated to this benefactor of humanity. I bet you can’t find it.

Yo tampoco he encontrado en ninguna óptica quien me dijera su nombre cuando pregunté por el inventor del sistema. Es triste ver la intranscendencia en la que nos disolvemos por mejores cosas que hagamos en beneficio de los demás, pero por contra he encontrado muchos héroes espada en mano, y calles con sus nombres, de la misma época que Alejandro della Spina. Tristemente matar siempre ha resultado más rentable.

When going into the opticians and asked who the inventor of the system was, nobody was capable of giving me an answer. It’s sad seeing the insignificance in which we dissolve ourselves for the good things we do in benefit of others, but instead I have found heroes, sword in hand, and streets with their name plates, from the same times as Alejandro dell Spina. Sadly, the killing has always been more profitable.

Pero el texto no es solo un merecido homenaje a Alejandro della Spina, sino también el punto de partida de una pregunta a la que no le encuentro una respuesta racional.

But the text is not just a tribute to Alejandro dell Spina, but also the starting point of a question to which I’ve not yet found a rational answer.

Voy a comenzar la colección 31 de mis trabajos sobre la Realidad Simultánea o Fotosimbolismo y, cada vez que busco la imagen precisa, cada vez que quiero entrar en mi mundo interior usando lo que me rodea, cada vez que presiento que ahí, en ese lugar frente a mí puede haber algo…, entonces me quito las gafas o miro por encima de ellas para descubrir los mundos ocultos que luego muestro en mis fotografías. Con gafas no los veo, solo los encuentro cuando miro directamente con los defectuosos ojos con los que nací y tanto odié. Sin nada ante ellos el mundo es mi mundo, y esto lo descubrí allá por 1991. Ya no sé si es un defecto o una bendición, pero sé que ahora no lo cambiaría.

Mis ojos son más inteligentes que yo, son un tesoro; ellos sabían desde siempre que yo tenía que ser, necesariamente, fotógrafo; pero tampoco sé por qué.

I’m about to start on my collection number 31 of my works on the Simultaneous Reality or Photosymbolism and, each time I search for that particular image, I’m wanting to enter my inner world using everything that surrounds me, every time I sense that there, in that place in front of me there could be something… Then I take off my glasses or I look over them to discover the hidden worlds I show in my photographs. With the glasses on I can’t see them, I can only find them when, with these imperfect eyes I was born with and hated, I look at them directly. Without hiding myself behind them this world is my world, and that is what I discovered back in 1991. I can’t say if it’s a flaw or a blessing, but I do know one thing, now I wouldn’t change it.

My eyes are more intelligent than I am, they are my treasure; they’ve known all along that I had to be, necessarily, a photographer, but I don’t really know why.

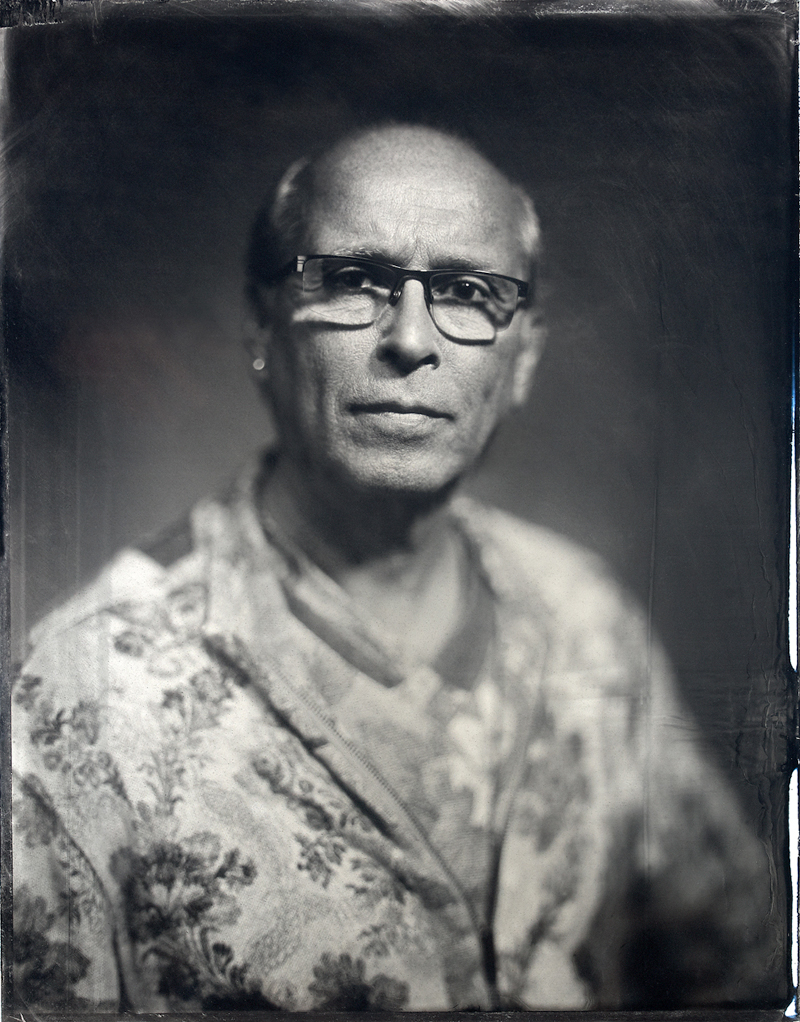

Retrato al colodión Humedo por Miguel Cruzado / Wet colodium portrait by Miguel Cruzado

Translated to English by Sandra Crundwell